During the hundred years of the Dutch Golden Age, flower paintings emerged as a genre of delight and desirability. The burgeoning middle class generated a demand for a dynasty of skilled painters. They infused religious and philosophical meaning into highly organized depictions of dozens of floral species. These arrangements felt abundant and wild, bursting at the seams. Each blossom is lit with dramatic ambiance and vies for attention against sumptuous velvety backgrounds.

One of the sought-after still-life painters was Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750), who began her illustrious career at fifteen and worked well into her 80s. Atypical of the period, she took the cut flowers out of the vase and placed the drooping stems on a stone slab, creating seemingly casual yet compelling compositions. One can trace the tension between the organic state and the obsessive control of Ruysch to the present-day artist Dominik Tarabański and his photographic series Roses for Mother.

From 2018 to early 2020, after finishing his day job as a fashion photographer, he was left with the vestiges: unwanted flower displays, plastic bags, metal clips, gaffer tape, fruit nets, rubber bands, and twist ties. With these materials, the photographer pivots to sculptor, substituting his animated human body for a withering floral object. Like the still lifes of the Dutch Golden Age, Tarabański constructs artful tableaus of beauty that belie an additional reading of melancholy and isolation. Leaning into an aestheticized anthropomorphism, he tapes and clips his subjects like a model of yesteryear. Tarabański contorts, stretches, and molds his flower characters with humor and pathos, reflected in sagging petals like bowed heads shedding tears.

Plucking the Petals

of Dominik Tarabański’s

Roses for Mother by Karen Wong

Plucking the Petals

of Tarabański’s

Roses for Mother by Karen Wong

Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750)

Still life of Carnations, Hibiscus, Morning Glories, and other flowers on a ledge, with a butterfly, undated, oil on canvas

Still life of Carnations, Hibiscus, Morning Glories, and other flowers on a ledge, with a butterfly, undated, oil on canvas

Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858)

Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750)

During the hundred years of the Dutch Golden Age, flower paintings emerged as a genre of delight and desirability. The burgeoning middle class generated a demand for a dynasty of skilled painters. They infused religious and philosophical meaning into highly organized depictions of dozens of floral species. These arrangements felt abundant and wild, bursting at the seams. Each blossom is lit with dramatic ambiance and vies for attention against sumptuous velvety backgrounds.

Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858)

Wagtail and Iris, 1830

woodcut print

One of the sought-after still-life painters was Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750), who began her illustrious career at fifteen and worked well into her 80s. Atypical of the period, she took the cut flowers out of the vase and placed the drooping stems on a stone slab, creating seemingly casual yet compelling compositions. One can trace the tension between the organic state and the obsessive control of Ruysch to the present-day artist Dominik Tarabański and his photographic series Roses for Mother.

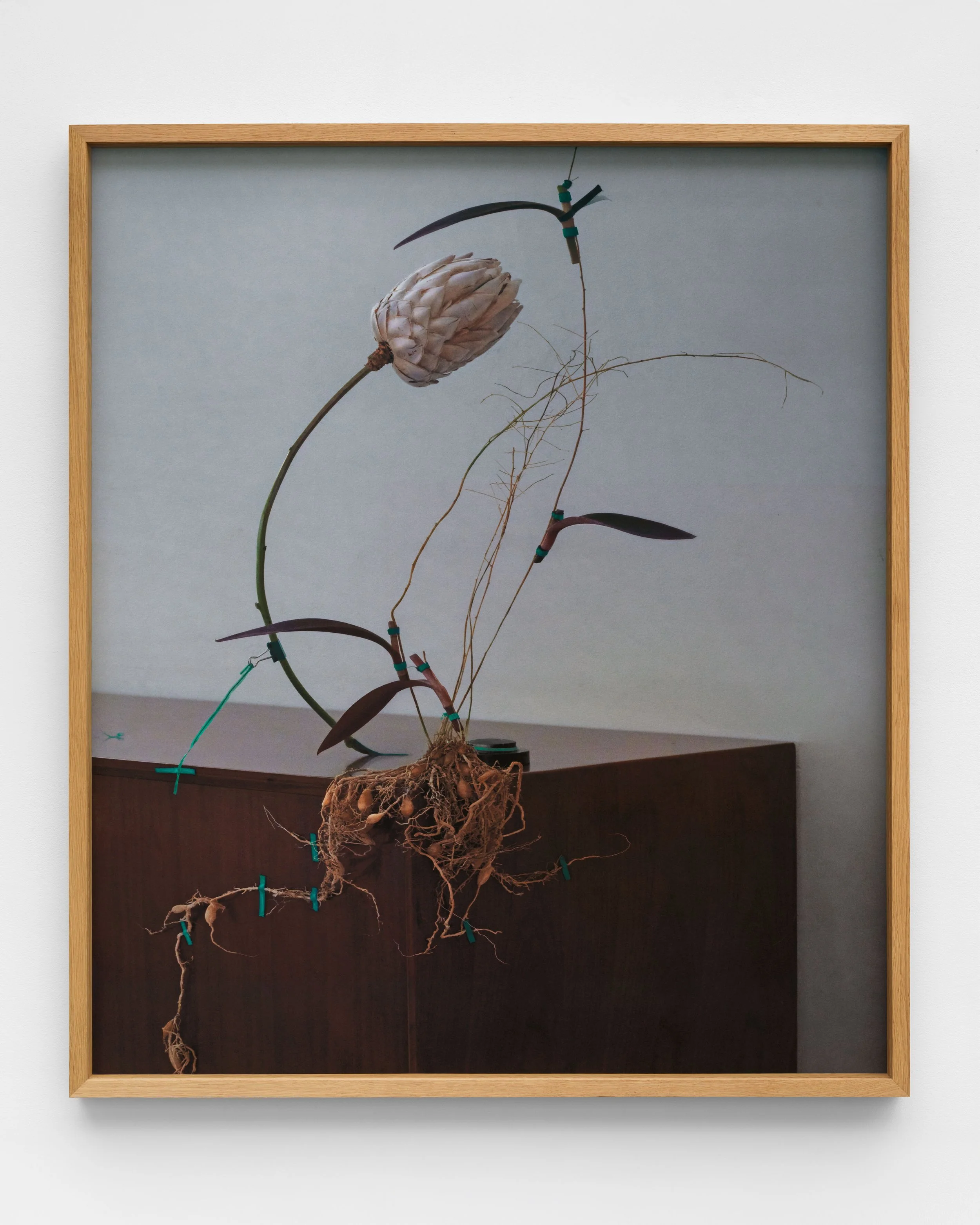

From 2018 to early 2020, after finishing his day job as a fashion photographer, he was left with the vestiges: unwanted flower displays, plastic bags, metal clips, gaffer tape, fruit nets, rubber bands, and twist ties. With these materials, the photographer pivots to sculptor, substituting his animated human body for a withering floral object. Like the still lifes of the Dutch Golden Age, Tarabański constructs artful tableaus of beauty that belie an additional reading of melancholy and isolation. Leaning into an aestheticized anthropomorphism, he tapes and clips his subjects like a model of yesteryear. Tarabański contorts, stretches, and molds his flower characters with humor and pathos, reflected in sagging petals like bowed heads shedding tears.

Tarabański’s ability to choreograph his flower subjects recalls the work of Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858), the last master of the ukiyo-e tradition. Hiroshige’s woodblock prints and paintings often depicted flora, fauna, and landscapes of his travels. In his renderings of branches, birds, and fishes, Hiroshige employed strong diagonals that produced a sense of urgent movement. He was undoubtedly instructed by the tradition of ikebana (making flowers alive), emphasizing the totality of the floral specimen. Having spent significant time in Japan, by osmosis or deliberate homage, Tarabański uses a minimalistic language as Hiroshige, highlighting the slant of a leaf or the angle of a twig. His photographic results eschew the symmetry of classical flower arrangements for something stranger and operatic.

One usually doesn’t associate sounds with flowers as foliage is silent in its ability to convey a range of dispositions. German artist Isa Genzken defies this broad assumption in her series of monumental public sculptures, Roses and Two Orchids. Three-story-high steel structures clear their throats and announce, “I am flower, see me roar.” By isolating each floral stalk and concentrating on nature’s architecture, Genzken achieves a sentinel-like authority through towering heights. Tarabański also leans into the flower’s structure and engineers a voice by manipulating his specimens as puppets — stems outstretched, buds singing in unison, and a bloom calling out for love.

The enchantment of Roses for Mother is the ritual before Tarabański snaps the photograph, an archival product of an arduous creative process with numerous false starts and finishes. These diorama meditations require him to possess a variety of skill sets; perhaps the most natural one is akin to that of a fashion designer. Key to the trade is the sculpting technique of draping fabric over a mannequin until a form materializes, such as balloon trousers or a couture dress.

Tarabański’s ability to choreograph his flower subjects recalls the work of Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858), the last master of the ukiyo-e tradition. Hiroshige’s woodblock prints and paintings often depicted flora, fauna, and landscapes of his travels. In his renderings of branches, birds, and fishes, Hiroshige employed strong diagonals that produced a sense of urgent movement. He was undoubtedly instructed by the tradition of ikebana (making flowers alive), emphasizing the totality of the floral specimen. Having spent significant time in Japan, by osmosis or deliberate homage, Tarabański uses a minimalistic language as Hiroshige, highlighting the slant of a leaf or the angle of a twig. His photographic results eschew the symmetry of classical flower arrangements for something stranger and operatic.

Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750)

Isa Genzken (1948)

Isa Genzken (1948)

Two Orchids, 2014/2015 Cast aluminum and stainless steel, lacquer, Courtesy of Parrish Art Museum

Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750)

Still Life with Rose Branch, Beetle and Bee. 1741, Oil on canvas, Courtesy of Kunstmuseum Basel

One usually doesn’t associate sounds with flowers as foliage is silent in its ability to convey a range of dispositions. German artist Isa Genzken defies this broad assumption in her series of monumental public sculptures, Roses and Two Orchids. Three-story-high steel structures clear their throats and announce, “I am flower, see me roar.” By isolating each floral stalk and concentrating on nature’s architecture, Genzken achieves a sentinel-like authority through towering heights. Tarabański also leans into the flower’s structure and engineers a voice by manipulating his specimens as puppets — stems outstretched, buds singing in unison, and a bloom calling out for love.

The enchantment of Roses for Mother is the ritual before Tarabański snaps the photograph, an archival product of an arduous creative process with numerous false starts and finishes. These diorama meditations require him to possess a variety of skill sets; perhaps the most natural one is akin to that of a fashion designer. Key to the trade is the sculpting technique of draping fabric over a mannequin until a form materializes, such as balloon trousers or a couture dress.

Tarabański sorts his day shoots remnants and spends hours nipping and tucking his flowers with clips and tape. In New York 2018, a wine cork is a counterweight for four pods of tiny floral spikes of Banksia hookeriana, a well-regarded blossom in the cut flower industry. Minute rubber bands hold the twigs in place while Tarabański draws viewers’ eyes down to the roots with a single unopened Cyclamen bud. The artwork suggests that all life is a balancing act. The tortured composition of West Bengal 2020 features arcs combating verticals as a shriveling Etlingera blossom stands in for a fading sun, all while the cantaloupe moon readies for orbit. In Paris 2018, a metal clip holds together an unlikely pair — a Medinilla magnifica with regal leaves embracing the delicate Lilium candidum. The Medinilla’s stork-like stance protecting the foundling gives rise to the motivation of this series: a son’s bond with his mother.

—

Karen Wong is the New Museum's Chief Brand Officer and a GSAPP Adjunct Assistant Professor at Columbia University.

She is the co-author of Made by MSCHF published by Phaidon in March 2025.

Tarabański sorts his day shoots remnants and spends hours nipping and tucking his flowers with clips and tape. In New York 2018, a wine cork is a counterweight for four pods of tiny floral spikes of Banksia hookeriana, a well-regarded blossom in the cut flower industry. Minute rubber bands hold the twigs in place while Tarabański draws viewers’ eyes down to the roots with a single unopened Cyclamen bud. The artwork suggests that all life is a balancing act. The tortured composition of West Bengal 2020 features arcs combating verticals as a shriveling Etlingera blossom stands in for a fading sun, all while the cantaloupe moon readies for orbit. In Paris 2018, a metal clip holds together an unlikely pair — a Medinilla magnifica with regal leaves embracing the delicate Lilium candidum. The Medinilla’s stork-like stance protecting the foundling gives rise to the motivation of this series: a son’s bond with his mother.

—

Karen Wong is the New Museum's Chief Brand Officer and a GSAPP Adjunct Assistant Professor at Columbia University.

She is the co-author of Made by MSCHF published by Phaidon in March 2025. x

Roses for Mother

Medinilla magnifica, Lilium candidum and a metal paper clip

Paris 2018

Paris 2018

Rosa kordesii, metal paper clips, gaffer tape, and rubbers

London 2019

London 2019

Warsaw 2018

Alstroemeria ligtu, paper tape, rubber bands, a metal clip, a plastic net, a plastic tie, and glass

Singapore 2020

Woodstock 2018

Singapore 2020

Phalaenopsis, Cortaderia selloana, Ipomoea batatas, Prūnum, tape, a rubber band, paper straw

Brooklyn 2018

Brooklyn 2018

Copenhagen 2020

Phalaenopsis, Zantedeschia, a metal paper clip, a twist tie and a gaffer tape

Stockholm 2018

West Bengal 2020

Stockholm 2018

San Diego 2020

Copenhagen 2020

Copenhagen 2020

Proteaceae Protea, Tradescantia pallida, Asparagus aethiopicus, a tape, a metal clip, a twist tie

West Bengal 2020

Etlingera, Heliconia rostrata, cantalupo, a gaffer tape, a quill, a nylon wire and rubber bands

Singapore 2020

Strelitzia nicolai, Heliconia rostrata, a gaffer tape and rubber bands

Singapore 2020

Brooklyn 2018

Nepenthes alata, Lathyrus odoratus, Iris germanica, a gaffer tape, and rubber bands

Woodstock 2018

Woodstock 2018

Tokyo 2019

Metrosideros excelsa, Papaver somniferum, Hippeastrum amaryllidaceae and a rubber band

Warsaw 2018

Warsaw 2018

London 2018

New York 2018

Annona muricata, Paeonia officinalis, gaffer tape, a rubber band and a metal clamp

London 2018

Nelumbium speciosum, gaffer tape, twist ties, metal paper clips, and rubber bands

Himalayas 2020

Himalayas 2020

Banksia hookeriana, Cyclamen a gaffer tape, a wine cork, and rubber bands

New York 2018

New York 2018

Stockholm 2018

Singapore 2020

Strelitzia nicolai, Heliconia rostrata, a gaffer tape and rubber bands

Singapore 2020

Paeonia lactiflora, Anthurium, gaffer tapes, a cotton rope, plastic nets, two marble cylindersties

San Diego 2020

San Diego 2020

London 2018

Strelitzia, a gaffer tape, a plastic bag, and a marble cylinder

Miami 2019

Miami 2019

Cotinus coggygria, Iris germanica, a gaffer tape, metal paper clips and rubber bands

New York 2018

New York 2018

Exhibitions

2025

Ross + Kramer

New York, USA

2025

WSA

New York, USA

2022

Zitadelle Spandau Centre for Contemporary Art

Berlin, Germany

2020

The Gallery of the National Philharmonic Hall

Szczecin, Poland

2019

6x7 Gallery Warsaw

Warsaw, Poland

1. Paris 2018

2. Copenhagen 2020,

3. West Bengal 2020

4. New York 2018

5. New York 2018

6. Singapore 2020

7. Avery Island 2019

8. Stockholm 2018

9. Brooklyn 2018

10. Woodstock 2018

11. Warsaw 2018

12. San Diego 2020

13. New York 2020

14. Singapore 2020

1. Paris 2018 — 2. Copenhagen 2020, — 3. West Bengal 2020 — 4. New York 2018 — 5. New York 2018 — 6. Singapore 2020 — 7. Avery Island 2019 — 8. Stockholm 2018 — 9. Brooklyn 2018 — 10. Woodstock 2018 — 11. Warsaw 2018 — 12. San Diego 2020 — 13. New York 2020 — 14. Singapore 2020 — 15. London 2019 — 16. Himalayas 2020 — 17. Key West 2019 — 18. Miami 2019 — 19. London 2018 — 20. New York 2018 — 21. Tokyo 2019

15. London 2019

16. Himalayas 2020

17. Key West 2019

18. Miami 2019

19. London 2018

20. New York 2018

21. Tokyo 2019

Inquiries

For additional information, catalogue, or acquisition inquiries, please get in touch.

For additional information, catalogue, or acquisition inquiries, please get in touch.